Is the significance of a speech defined by who says it? How many people hear it? What is said? Or what that voice comes to represent?

Arguably one of the most powerful and enduring speeches in U.S. history, particularly during the Civil Rights Movement, is Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream.” It continues to echo through American life not just because of its vivid language, but because the dream itself remains unfinished. We know the footage, the crowd, the cadence of his voice. Yet knowledge about something is not the same as experiencing or understanding it.

In the modern climate, fall of 2025, social inequalities and civil rights are on full blast. Protests can be seen locally and live all around the nation. Even outside the comfort of our “United” States, all around the globe, injustice rains in every shape and form. There are many more than just MLK’s dream being dreampt. The biggest is that all of this is just a dream; however, in reality, more of a nightmare for millions around the world.

The VR experience MLK: Now is the Time, produced by TIME Immersive, reframes that understanding. Rather than recreating 1963, it pulls the user into a modern interpretation of ongoing civil rights struggles—housing, policing, and voting—through immersive, symbolic environments. It transforms viewers from observers into participants, asking not what King dreamed, but how we continue that dream now.

Anthropologically, this is profound. VR becomes a cultural space of memory and embodiment, where history, identity, and emotion converge. The virtual artifacts—game pieces, steering wheels, ballots—aren’t just visuals; they’re symbols that expose the living structures of inequality. Yet the most powerful lesson isn’t what you see, but what you feel standing inside it.

Stone of Hope

Before anything else, the experience has you set aside your hand controllers as the VR uses hand tracking, allowing you to interact with the virtual environment using your own hands. To begin, a protest sign is held in front of you with a fist raised in the air, prompting you to do the same, and to start your journey through the fight for empowerment and civil justice.

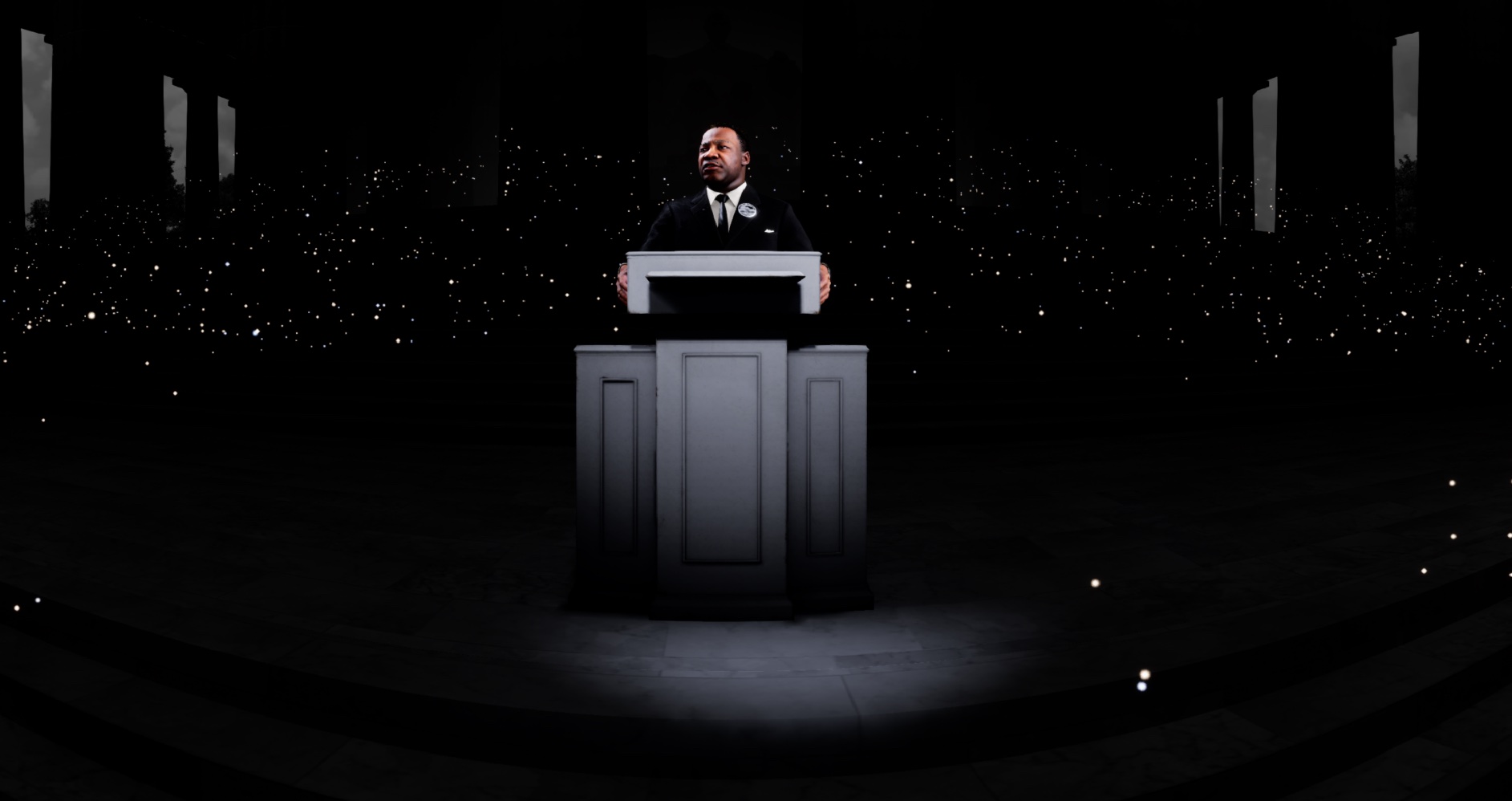

You are then brought to the Lincoln Memorial, facing the stairs and back to the reflection pond. Echoes of marches and King’s voice boom through the headset. Floating lights shimmer like small flames surrounding you, and dance around the memorial. From a massive stone emerges King’s carved likeness as his words build, until one fragment hurtles towards you. When you reach out and catch it, the world shatters into light, and your passage to the deeper layers of the experience begins.

Part I — Housing

The first destination is a “game” that begins as a distorted play of Monopoly. You play as the black house; your opponent, the white one. Each draw of a card brings another reminder of inequality, watching the corners of the board shift from the simple pieces to full neighborhoods. One clean and thriving and lively, the other fenced in and choked by pollution.

At first glance, it looks like nothing but a game. Then, frustration sets in. The outcome isn’t random; it’s rigged. You’re not losing by luck—you’re losing by design. That realization hits hard. Even in virtual form, the helplessness is tangible.

This scene transforms the abstract idea of redlining into a lived experience. It illustrates how discrimination operates not as isolated acts, but as a system written into the “rules” of American life. From an anthropological lens, the board becomes an artifact of structural violence—a playful, unsettling reminder that homeownership and opportunity have long been distributed unequally.

Part II — Policing

The next moment is jarring. Darkness. Headlights. Then, the piercing sound of sirens and the glow of red and blue lights. You’ve been pulled over.

Before the officers appear, the words of a concerned mother are played for you. Expressing her fear for her young, black son in a world of targeted structural violence. Her heartfelt words left me thinking, why should a mother tell her child not to be themselves? Why should people act in such fear that they can not be their beautiful, authentic selves in this world? It’s because of the lights that continue to flash before your eyes as these words are played. It makes the virtual car you’re sitting in feel claustrophobic, and the air dense with the tension of uncertainty.

Upon seeing the officers’ silhouettes, even knowing it’s virtual, I felt my pulse quicken. As the one set of officers stands in front of you, the second set, from behind, steps to your windows. One passenger side, the other right next to you. Shining their bright flashlights directly in your face. He says he’s going to run your plates and to keep your hands on the steering wheel. As if you didn’t, you’d leave with virtual handcuffs, or worse, a bullet hole. The seconds last longer than they should, the illusion of control slipping away as your hands tighten around the virtual wheel. But once you feel a slight sense of calm among the nerves, and your grip loosens around the non-existent wheel in front of you, the flashlights are instantly back in your face, and the holsters around the officer’s belts are grabbed. In no time, my hands found themselves trying to grip the wheel tight enough for my knuckles to turn white.

For many, this moment mirrors reality. For others, it offers a rare glimpse into the vulnerability that defines everyday life for those targeted by systemic bias. The brilliance of this sequence lies in its immediacy—it refuses emotional distance. You can’t analyze safely from the outside; you must feel from within, from the “driver’s set”. This is not just a reenactment; it’s an embodied anthropology of fear. You move beyond the cognitive and emotional state of anxiety and can feel it physically. You are fully experiencing fear brought about by a broad social structure, and living through the power dynamic of two people who are not biologically or inherently different.

Part III — Voting

The voting sequence shifts tone, at first starting behind closed curtains, you see and hear of different ways the black community has been restricted and deferred from being able to cast a ballot. Once the curtain drew open, you find yourself just out of reach of a ballot box, centered around towering pillars labeled education, law, police, medicine, labor, and housing, linking all the pillars like the heart of a fragile structure.

Dancing in front of you is a registration sheet, but the closer you get to the chance to grab it, it slips away. Constantly mocking you. As you continuously try to grab the sheet, the ceiling begins to fall, the ground splits in two, and the pillars begin to fall, taking you with them. Down the rabbit hole of “democracy” that wants to keep down those they see as unworthy.

This moment captures voting as ritual: an act that defines belonging but can also mark exclusion. The VR space makes that dynamic visible. Disenfranchisement becomes not just political, but cultural—a denial of recognition. It reframes the ballot not as a piece of paper, but as an instrument of collective power and autonomy.

Part IV — Now is the Time

The final environment is hauntingly beautiful—broken stones, torn signs, scattered coins, and then, a sliver of light. Hearing King’s voice ring in the mist of destruction, listening to his plight with nothing but piles of wreckage, it felt like hope, like everything broken can and will be rebuilt.

Without prompting, I raised my fist in the air. It wasn’t a decision; it was instinct. In that motion, the line between digital and real disappeared. For a moment, I wasn’t just witnessing resistance—I was part of it.

This is what anthropologist Victor Turner called communitas: a fleeting sense of unity that transcends social boundaries. The scene becomes a ritual of participation, a collective acknowledgment that King’s dream is unfinished but alive. It’s not about revisiting the past; it’s about continuing it.

One Final Reflection

Closing the experience, you are taken back to the pond where MLK’s carved bust floats in front of you, disappearing as sequences of his speech play and roll into protests, from the black and white to the wonderfully colored. Then, you are looking out towards the pond and the Washington Memorial, looking at all the floating lights. A reflection of yourself, raising your fist alongside thousands of others, who have come to understand the true message and reality of civil rights, and the true effect systems have not just on one people or some people, but a whole community we live so close to.

Virtual Reality as Memory Work

MLK: Now is the Time doesn’t recreate history—it revives it. It transforms the March on Washington into a living mirror, reflecting the persistence of inequality and the urgency of action. Here, VR functions as memory work: a space where remembrance becomes responsibility. It translates what we know into what we can feel, collapsing the distance between learning about history and standing inside it.

This experience, though completely different in the idea they try to convey, held a similar feel to EMPEROR. When you are immersed in the narrative of the VR and able to forge a connection, beyond internet access, you can feel and understand the message of the experience. When playing as the father in EMPEROR, you feel and sense his struggle as he moves through life, now affected by aphasia. And while moving through the parts of MLK: Now is the Time as an active participant, you further see the injustice and civil work going into a historic struggle. Both worlds may be virtual, but their ideas and narratives are real, and so is the empathy felt from going through both of them.

The experience lasted roughly twenty minutes; however, I became fully immersed in it, and I lost all track of time. When I removed the headset, I didn’t just return to the present—I carried the experience with me. It wasn’t just about civil rights; it was about self-reflection. The simulation asked not what King dreamed, but what I will do with that dream now. The power of this VR experience lies in how it reclaims empathy as education. It reminds us that the dream was never meant to fade into black-and-white footage. It was meant to be rebuilt, reimagined, and relived—until equality is more than an ideal.

Because truly, now is the time.